“Try as you may, there is no historical event that cannot be recast as the result of economic class struggle, and there is no psychological observation that cannot be interpreted as being caused by an unconscious obsession with sex. [Freudianism and Marxism], in other words, are too broad, too flexible with respect to observations, to actually tell us anything interesting. If a theory purports to explain everything, then it is likely not explaining much at all.”

-Massimo Pigliucci[1]

Your beliefs are your mental model of the world. When you see something happen in the world, your beliefs can often give you a way to explain it. You see water droplets turn sunlight into a rainbow. You watch salt disappear into water. You hear guitar strings making various sounds. If your beliefs about how the world works include concepts like refraction, wavelengths, atoms and molecules, dissolution, vibration, and resonance, then these are all phenomena that you could explain in terms of your beliefs.

But having a good mental model of the world isn’t just about being able to explain things. Just as important – perhaps more important – are the things your beliefs can’t explain. Rainbows, salt water, and guitar sounds are things you aren’t surprised to see in the world, and this is because your mental model of the world includes them, it allows for them to happen. But there should also be things that your model of the world doesn’t include, things that you believe are not possible. In other words, your beliefs should narrow down the list of possible things you expect to observe.

Explanation isn’t about coming up with a story that nicely frames an observation. Explanation is about seeing how everything fits into the patterns and regularities of the world. It’s about answering the question “What do the rules allow and what do they not allow?” If your mental model of the world is able to account for any possible observation, then it doesn’t actually provide an explanation, at least not in the sense of an understanding. It only provides an explanation in the sense a story; it lets you tell fairy tales and fables about the things you observe.

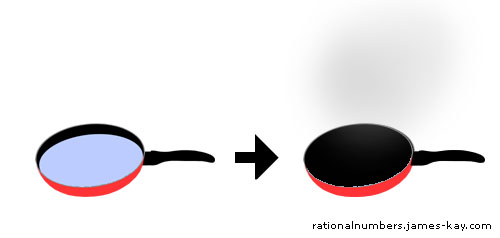

Imagine I put some water into a hot frying pan. A few minutes later there is no water left in the frying pan:

Perhaps your model of the world says, “Aha! Heat from the frying pan went into the water and evaporated it into steam.” You have explained the observation in terms of your beliefs about how the world works.

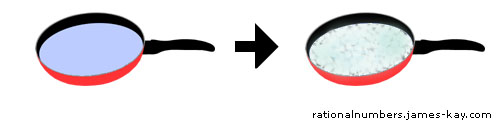

But what if you had observed another outcome? What if the water in the frying pan had turned into ice?

If your beliefs are merely a way of generating stories about what you see, you might think something like “Aha! Heat from the pan caused water to evaporate, and evaporation removes heat, which caused the water to freeze.” This sense of belief, as story-generator, seems to be able to explain both outcomes equally well. This is problematic.

If your beliefs are really concerned with trying to understand the world, they should only be able to explain one outcome, and the result of seeing an unexpected observation should be puzzlement. Your model should say “Hmm…that’s not what I expected to happen. Something must be wrong.” When we observe something that our model says is impossible (or at least unlikely) we should be confused by this. Your beliefs should make predictions, they should cause you to expect certain things to happen, and to expect other things not to happen.

Story-generator beliefs probably served to comfort to our most primitive ancestors. They weren’t able to explain what stars were or what caused lightning because their beliefs didn’t include concepts like nuclear fusion or electric charge. They made up stories to explain these, stories of capricious gods and invisible demons. These stories didn’t make predictions in advance or provide ways to test their truth, they just served as comforting fables. Perhaps groups of humans that had good explanatory stories and comforting fables were more likely to survive than those that didn’t, which would explain our modern predisposition for believing good stories[2].

But there are two problems with story-generator beliefs. The first is that they can only explain something after it has happened. If a belief can explain seeing the water boil into steam just as easily as it can explain seeing the water freeze into ice, then it doesn’t tell you which one to expect ahead of time. The second problem is that if your beliefs can explain any possible observation, you have no way of knowing if those beliefs are true or false because you have no way to test them.

The most important concept in science – indeed the most important concept about knowledge in general – is that ideas are tested by observation. We test ideas by comparing what they predict with what we actually observe to happen. Beliefs that don’t make predictions about what you should expect to see give you no way you could even know them to be true in the first place.

A final note: the idea that our predisposition to believe comforting stories is an evolutionary adaptation may be an interesting one, but if it doesn’t make testable predictions or provide ways to falsify it, it may itself be just another example of a comforting fable. This is a problem with many of the ideas that have come out of the field of evolutionary psychology.